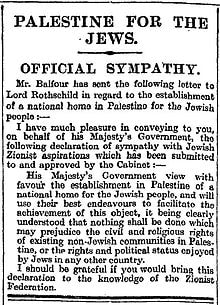

by Rabbi Harold J Kravitz, Rosh Hashanah Day 1 Sermon, 5778 Earlier I mentioned that this year marks the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, which set into motion the creation of the State of Israel, as well as the 50th anniversary of the Six Day War that has brought Israel to the challenging place in which she finds herself. And of course this coming May will mark the 70th anniversary of the founding of the State. There is one other less well known anniversary being observed this year that I think our synagogue also has good reason to acknowledge. In 2018 the Masorti Movement in Israel will be celebrating 40 years since it was successfully launched through efforts credited to Rabbi Michael Graetz, who for decades served as rabbi of our sister synagogue Magen Avraham in Omer.  I am delighted that we had the opportunity to honor Rabbi Graetz here at Adath this past April when we hosted the national benefit for the Foundation for Masorti Judaism. It was a privilege for me, Prof. Louis Newman and Rabbi Amy Eilberg, to be honored together with Rabbi Graetz who has done truly heroic work in founding our Movement in Israel. The benefit was a great success selling out and raising more than was expected. The Masorti Benefit could not have happened without the tremendous leadership of Heidi Schneider and Kim Gedan, co-chairs of Adath’s Israel Committee to whom we owe a deep debt of gratitude. I especially want to take this opportunity to extend hakarat hatov- deserved recognition to our congregation for its many years of support of the building of the Masorti Movement in Israel and then I want to use this as an opportunity to reflect on the successes and challenges we face as we mark this anniversary. Hosting this national benefit at Adath is a high point in a long history of support for the Movement by our congregation that goes back well before the Movement was officially established. In the mid-1970s Rabbi Graetz would stop over in the Twin Cities on his way to his home town of Lincoln, Nebraska to elicit the support of the rabbis here in the work he was doing to spread our approach to Judaism in Israel. When I arrived here I was impressed to learn of our close ties to Omer. Working with then member Avi Bar- Cohen, we felt it would be important to expand Adath’s commitment from that of supporting a single sister congregation to the support of a movement. The hand- out you received today describes a Masorti Movement that has grown steadily, shifting from an ideology imported by Jews of the diaspora to a Movement, the majority of whose members are now Israelis. When our family was on sabbatical in Israel in 2003 we got to visit with the Graetz family in Omer. Rabbi Graetz showed us plans for building an addition needed for their growing congregation. I felt that Adath could assist with the building of their security room, an unfortunate necessity in Israel, especially for a building within missile sight of Gaza. It took us two years, but we met that goal. It was incredibly powerful a number of years later to hear Rabbi Graetz’ successor Rabbi Gil Nativ describe the importance of that contribution. He told us about a wedding that had been planned for the synagogue when war broke out with Gaza. As missiles were falling in the area, the huppah could only proceed because it was moved into the security room that Adath congregants had made possible. Many of us have since contributed to the construction of a second shelter built to accommodate the growing needs of the congregation during Rabbi Sadoff’s tenure. After we fulfilled our commitment to building that first security room, we determined a path for not only benefiting the synagogue in Omer, but for building the entire Masorti Movement. Rabbi Graetz had established an internship program at Magen Avraham for rabbinical students from the Schechter Institute in Jerusalem, to spread our approach to Judaism around the country. Since 2005 Adath Jeshurun has been primarily responsible for funding that program, which has been a blessing to the growth of our movement and to the development of talented young rabbis willing to take on the challenges of providing an approach to Judaism that is both deeply rooted in our tradition, yet responsive to contemporary challenges, as Judaism has always been. This summer Cindy and I got to be in Israel. A highlight of our trip was getting to be with some of the amazing people who have come through Magen Avraham’s Rabbinic Intern program. Let me tell you about some of them. An exceptionally gifted former rabbinic intern from the program in Omer is Rabbi Tamar Elad Appelbaum who succeeded Rabbi Graetz as the Rabbi of the Congregation in 2005 before moving on to other roles. She was named in 2010 by the Forward as one of the five most influential female religious leaders in Israel for her work promoting pluralism and Jewish religious freedom. She has since founded a thriving congregation in the Baka neighborhood of Jerusalem called Zion that seeks to bridge diverse Jewish cultural quarters of Jerusalem in her Masorti affiliated Congregation. Her reach extends beyond the Jewish community as she is well known as a bridge builder in the city of Jerusalem.  I am not sure if you know that Yom Yerushalayim- the day marking the recapture of the Old City 50 years ago has become a source of great controversy. In what is known as the March of the Flags, religious nationalist groups organize tens of thousands of teenagers to march through the Muslim Quarter of the Old City on Jerusalem Day in triumphant celebration. Disturbingly, marchers are known for taunts and threats to the Arabs who live along the route. It is an ugly side of Israel, which should truly embarrass us as Jews. In her effort to dream of a different kind of Jerusalem Rabbah Tamar , as many call her, has initiated another kind of gathering on Yom Yerushalayim that draws hundreds of people to the First Train Station, the popular gathering place in Jerusalem where she is well known for the Friday night service she leads. On Yom Yerushalayim she brings Jews, Christians and Muslims together who are interested in building a society that is based on mutual respect. Rabbi Elad-Appelbaum has said about the event, “We all felt that this is the Jerusalem we want, this is Jerusalem Day for all of us, the Jerusalem that we dream about.” That is the kind of religious leadership we have helped foster in our support for the training of Masorti rabbis in Israel. In addition to attending the inspiring Kabbalat Shabbat service at the Zion Congregation, another highlight for Cindy and me was getting to have coffee in Jerusalem with the two rabbinical students from the Schechter Rabbinical School who presently serve our sister synagogue Magen Avraham in Omer. They are Nava Berenshtein and Yosi Baruch, both highly impressive. Nava grew up in Petach Tikva to an Orthodox religious Zionist family. After receiving a theater degree in Jerusalem she spent three years in Los Angeles studying directing at UCLA. Teaching theater and Hebrew in LA religious schools she came to appreciate the approach to Judaism she found outside of the world of Orthodoxy that welcomed the full participation of women. She returned to Israel and registered at the Schechter Institute and is being mentored by our own Yonatan Sadoff.  Yosi Baruch has an equally compelling story. Born in Israel to a family who made Aliyah from Greece, Yosi pursued a successful career in Israel’s high tech industry. He became increasingly concerned about the state of Israel’s wellbeing. He was one of the hundreds of thousands of Israelis who took to the street in 2011 to protest the burden that the secular middle class was carrying in paying taxes and serving in the army, burdens largely not shouldered by the Ultra Orthodox sector. Encountering non-Orthodox rabbis involved in that social justice effort planted the idea of pursuing further Jewish studies that led him to rabbinical school in the Masorti Movement.  Finally, let me introduce you to Rabbi Dikla Druckman who was ordained this year at Schechter and who also served as a rabbinic intern in Omer. When we put together Adath’s meaningful joint trip to Poland with Magen Avraham three years ago, we had the privilege of having Dikla join us. Dikla’s path to the Masorti rabbinate began when she was approaching the age of Bat Mitzvah. Her mother asked her if she wanted to be called to the Torah, something “unheard of” in her secular community. Her decision to become Bat Mitzvah in a Masorti synagogue changed her life. She became active in the Masorti Movement Noam Youth group and eventually enrolled in Schechter’s rabbinical school. Now that Yonatan and his wife Meirav have decided to take a pulpit in Melbourne Australia, Magen Avraham has chosen Dikla Druckman as their next rabbi. We look forward to being able to welcome Rabbi Druckman to Adath in April and to continue to deepen the relationship we have started. The people I have spoken about today are doing heroic work in fashioning an Israel whose values are consistent with ours. The support many of us here at Adath have given has made a real difference in helping to develop these outstanding leaders and future leaders and so I thank you. There is a flyer on your seats describing the achievement of our Movement in the 40 years since it was formally established. There is so much work to be done. I thank you in advance for the generosity you will show to make sure that our Adath continues to thrive through your membership and your support of our L’chaim campaign on which we depend. Once you make that commitment, I hope that you will consider a gift for the work that still needs to be done in Israel through the Masorti Movement. I truly believe that Israel’s future as a Jewish and democratic state depends on us. In responding to this appeal we are making a powerful statement about the kind of Israel we dream of and want to see realized. I trust that you all have heard about the challenges we face and about the event of this summer in which Israel’s present government reneged on an agreement that would have permanently established a section of the Kotel that permits the kind of prayer we take for granted in our synagogue in which women are able to participate fully without being assaulted. You no doubt heard of the legislation before Israel’s Kenesset that would bar conversions done in Israel other than those approved by the Ultra Orthodox Chief Rabbinate. These are only the latest attempts to restrict diverse expressions of Judaism in Israel and are part of a pattern of undermining democracy in Israel. Any other country imposing such limitations on the practice of Judaism would be appropriately accused of anti-Semitism, but American Jews have put up with such insults for years. It was an outrage to hear this summer of the blacklist kept by the Chief Rabbinate of respected American rabbis of all movements rejecting their letters vouching for people’s Jewish identity. Rabbis such as Alexander Davis of Beth El and Morris Allen of Beth Jacob were on that blacklist. I have to admit to being a bit disappointed at not having been on the list. Maybe next year! Let us be clear that the challenges we face in confronting the Ultra Orthodox are not about their having better or more authentic ideas. They do not. Rather they have effectively parlayed their role as minority parties to successfully extract more than a billion dollars a year for their institutions. It is incumbent upon us as Conservative Jews to use every means and vehicle we have for influence on Israel to communicate loudly and clearly that we are fed up and will no longer tolerate such deplorable and disrespectful treatment. In the end it is clear that the most important voices to be heard will be those who are living in Israel who share our values and concerns. I am absolutely convinced that it is people like Tamar and Dikla, Nava and Yosi who represent our best chance for creating the kind of Israel that we hope for and dream of. We must have their backs in the sacred work that they are doing. A number of years ago I received a moving letter from Rabbi Michael Graetz following the brit milah of his grandson with which I want to conclude my message today. He was delighted to announce the good news and to describe the moving experience of the brit milah held during at a morning prayer service attended by about 70 people. Most were his son Tzvika’s fellow students at Schechter, or colleagues in the work of Jewish education in various parts of the Masorti enterprise in Israel. He writes, “Not only was there an unusual spirit during this service, but the sense of devotion was very clear… the naturalness of the service, along with the joy of participation in a mitzvah gave an atmosphere of comradeship, partnership and dedication…in what was for these young people a natural atmosphere of egalitarian Jewish religious experience. In addition, the words spoken revealed Jewish life which had a Universal flavor side by side with a deep commitment to Jewish texts and traditions.” One of those attending, an uncle of Rabbi Graetz’ daughter-in-law Shirly…he is a director of a large kibbutz corporation (I assume a secular one), was moved. [Her Uncle Humi] (He) came up to Michael and said that “he was not sure what he was seeing and what he was feeling. This was not the way he had experienced Judaism up until now. It was different, and did not seem to contradict his kibbutz and Zionist values. He felt confused. Where is this coming from? He felt elated. If the face of Judaism in Israel was this way, he ruminated, how different our State would be?” He was worried and told Rabbi Graetz "you have to work much faster to inculcate this kind of Judaism in our society, time is running out." Rabbi Graetz goes on to write: “It was a sobering moment for me. I recalled my own awakening to the depth of ignorance of and alienation from major Jewish values rampant in Israeli society. It was during my service in the Yom Kippur War 30 years ago. It was the major reason for my coming to Omer to work with "the people" in a congregational framework. I told the assembled young people, the close friends of my son and daughter, how being in that room was like a dream fulfilled. A group of young people like this was not even a dream when I began in Omer. I had seen it happen, and even better, I had seen my grandson born into that reality…” Rabbi Graetz went on to cite a teaching of our colleague, my teacher, Rabbi Reuven Hammer who has commented on words from Psalm 126 that we read on Shabbat before reciting Birkat HaMazon- - “hayyinu ka-holmim” we were like dreamers- “that the root of the word "chalom", which means dream, is also the root of the word "le-chahlim", which means to be healed. In this view the dream is a healing, or the return of the Jewish people to its land is a process of healing. It may seem like a dream, but the reality is that it heals. His feelings at his grandson’s brit that day were those of healing. He truly felt, as did Shirly's uncle Humi …the expression of Jewish values rampant in that room: respect, egalitarianism, God, Jewish law, compassion, friendship, loyalty, creativity, openness, inclusivity, and responsibility contained the power to heal Israel.” Now if we only had the means to hurry the job up as Humi suggested.We still need to pursue that dream, because with that work the "chalom" the dream becomes reality, and it is that reality which will bring about "chalamah", healing. The work that Rabbi Graetz writes of and in which he played such an important role continues. The materials you have received convey it. The concerns that Uncle Humi expressed 14 years ago remain. We need to hurry up if we are to make inroads to continue to shape Israel in the vision of what it could be. Hayenu Cholymim – let us continue to be like dreamers for that kind of Israel.  Intro to the Torah Reading Rosh Hashanah Day 1 5778 The 100th Anniversary of the Balfour Declaration Reading it we cannot help but see the way it resonates with issues that still confront the region where our ancestors’ story unfolded, as is stated so well in the comment in our Machzor on the top right of p.102. The Torah reading today begins with a family conflict that our mother Sara had with the concubine Hagar who gave birth to Abraham’s first child Ishmael, lest he compete for the inheritance with her son Isaac. The parasha ends with a description of the tribal conflict between Abraham and Avimelech over how these tribes dealt with the land around Beer Sheva and with access to water. The competition over this place has not ended. This November marks the 100th anniversary of a significant document that laid the ground work for the creation of the State of Israel. It also contributed to the ongoing conflict over that land. On Nov 2, 1917, to the delight of the early Zionist Movement, the British government put in writing its endorsement of the establishment of a Jewish home in Palestine. The Zionist leaders who received it enthusiastically had no idea how complicated things would become on the path to found the State of Israel, which celebrates its 70th anniversary this coming May. That declaration reads: Foreign Office November 2nd, 1917 Dear Lord Rothschild, I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty's Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by the Cabinet. His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country. I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation. Yours, Arthur James Balfour The story behind the Balfour Declaration and Great Britain’s motivation for making such a declaration is a fascinating one that is well told in Jonathan Schneer’s The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict (2010). At the same time that the British government was making promises of support to the Jewish people of assistance so we might realize our hopes for a return to our homeland, they were making other promises that would set into motion the conflict as it developed. British and French diplomats Mark Sykes and George Picot (pee-ko) had secretly agreed that after World War I that the British would divide the land of Palestine, and the broader region, giving the French control of the Northern section the Jews hoped would become ours under a British protectorate. Furthermore promises were being made to Sharif Hussein of Mecca that in exchange for uniting the Arab tribes in the war on the side of the allies, he would get to rule an Arab Nation that he was led to believe would include Palestine. These contradictory promises contributed significantly to the profound conflict with whose consequence we are still grappling. The vying for the land now controlled by the Jewish State has deep roots in history. Would that we could come up with a peace treaty as elegant as the one Abraham established with Avimelech to resolve their dispute. Before Musaf RH 1 5778 “Catch ‘67” As we are about to begin the Musaf Amidah with its prayers for wellbeing, there is so much that consumes our thoughts about the State of Israel, for which we prayed before sounding the shofar (p. 116) in this 70th anniversary year. We worry for Israel’s security knowing well the existential threats it faces. We heard them reiterated this week when the chief of Iran’s army threatened “We will destroy the [Zionist] entity at lightning speed, and thus shorten the 25 years it still has left.” He went on to say that any stupid move by Israel against Iran and they will “turn Tel Aviv and Haifa into dust.” What a lovely sentiment with which to start the year. Israelis are constantly debating the issue of how to confront its existential challenges. I got to see this again first hand this summer when Cindy and I were in Jerusalem. I will say more about that later. For now I want to tell you about a fascinating lecture we got to attend at the Sholom Hartman Institute. The lecture was delivered by Micah Goodman, an outstanding Jewish thinker on their faculty who has written a book that has been a best seller in Israel since being published in Hebrew in March. It is called Catch 67 and it raises critical questions about the meaning of the 1967 Six Day war, which took place 50 years ago this past June. Goodman’s book begins and ends with a well-known passage from the Talmud Eruvin (see tractate Eruvin 13b & Yevamot 14b). “For three years, there was a dispute between Beit Shamai and Beit Hillel [over halacha].” It was resolved when “a divine voice (bat kol) announced: ‘both are the words of the living God, but the Halacha… is with Beit Hillel.’” There are two bitter quarrels currently ripping apart the fabric of Israeli society. One is the political conflict between Right and Left that has been festering for 50 years, since the Six Day War. A second is the conflict between the religiously observant and the secular. As journalist Shlomo Maital explains in a thoughtful Jerusalem Post review, “Catch 67” is about the political dispute. (Read the story HERE) Goodman is working on a second, future book about the religious one. It was quite moving to be present to hear Goodman describe the terrible existential dilemma that Israel faces as it marks its 70th year. The two correct views according to Goodman are that: “The Right believes that withdrawing from the hills of Judea and Samaria will shrink Israel to tiny proportions, making it a weak and vulnerable country that will eventually collapse. The Left believes that the continued Israeli presence in the territories will crumble Israel morally, isolate it politically and crush it demographically… It appears [Goodman asserts] that both views are true. And because both are true, we are all trapped. As Woody Allen once said, “The world faces the disaster of a population explosion and environmental disaster,” Allen said, “or the holocaust of nuclear war. May we choose wisely.” It speaks volumes that Goodman’s book has become the most important book published in Israel this past year. In July, Israel’s Knesset sponsored a discussion of the book in which people of opposing views debated respectfully, which in itself is a miracle. Goodman’s thesis has been sharply challenged by former Prime Minister Ehud Barak as being too influenced by the right who Barak believes overstate the security risk of withdrawal. Barak’s critique makes it all the more profound to hear Goodman state, without mincing words, that “The occupation does not lead to a lack of morality, the occupation itself is immoral.” * Goodman is no political scientist, but as a philosopher he urges Israeli to struggle with hard questions. So what is the way Goodman proposes to escape the trap in which Israel finds itself? He suggests that a good place to start is to stop thinking in black and white terms about peace and about occupation. He urges us to consider instead what it would look like if Israel committed itself to more peace and to less occupation. Since his book at this point is available only in Hebrew you can read the many reviews available that convey what he thinks more peace and less occupation would look like. Let us come back to the text with which he begins and ends his book from the Talmud in Eruvin as journalist Shlomo Maital summarizes Goodman’s thesis. “Why, if both Beit Hillel and Beit Shamai were right, did halacha follow Beit Hillel? Because, Goodman explains, the students of Beit Hillel were first taught the views of Beit Shamai and listened to them with respect. Beit Shamai, in contrast, listened only to themselves. As with Shamai, the bitter political fight between Right and Left over Judea and Samaria and the settlements has become a dialogue of the deaf. We need to be able to listen to the Bat Kol that conveys the voice of the other.” “Jewish tradition is one of debate, of argument,” Goodman writes, in his book’s closing sentences. “But it is also one of listening to others – listening that can restore and elevate the culture of the Israeli dispute.” Maital writes, “I hope “Catch 67” will help us Israelis become listeners, rather than screamers. Can we restore the Beit Hillel tradition of reasonable discourse to our fractured political scene? Can Jews listen to one another? Can Jews listen to Palestinians – and vice versa? A peace agreement will begin with a small step toward empathy and dialogue, not a huge leap to an imaginary final deal.” As we start the Musaf service with the words of Hineni “Here I am” that Hazzan Dulkin will chant, we encounter a critical value that would help all sides get to the place of really listening- the value of humility which the Hineni embodies. Let us pray and act with humility. And if we can do so, let us hope that we arrive at the point with which the Musaf prayer ends - a vision for peace to carry us forward in the New Year. Comments are closed.

|

Who's writing?Adath clergy, staff, and congregants share Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed